Students experience a traditional Irish Halloween

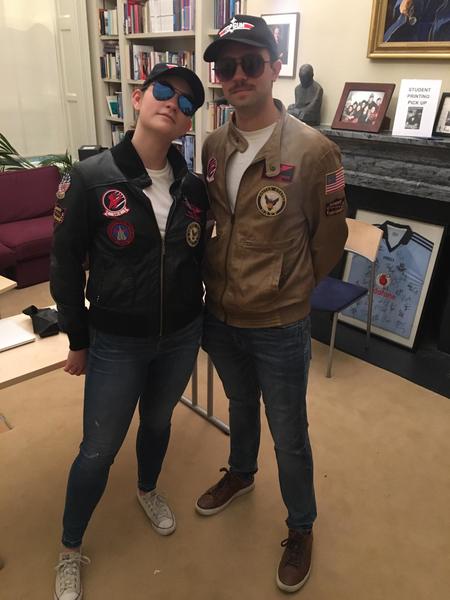

Staff at the Dublin Global Gateway dress up every year for the traditional Irish Halloween celebrations.

Staff at the Dublin Global Gateway dress up every year for the traditional Irish Halloween celebrations.

It is a little known fact beyond the craggy shoreline of the Emerald Isle that the North American holiday Halloween originates from an ancient Celtic pagan celebration—Samhain (an Irish word pronounced “sow-win”). Samhain, celebrated October 31st to November 1st, marks the midpoint between the fall and winter solstices, a time to gather the harvest and prepare for the long, dark evenings of winter.

In the ancient festival, when the harvest gathering was complete, communities would come together with Druid priests for bonfires—paying homage to the sun in thanksgiving for a bountiful harvest—and the ritualistic sacrifice of animals. Samhain was a period in which the Irish believed that the barrier between the human world and the spirit world broke down, allowing the dead—and more sinister beasts of the underworld—to roam the Earth. Many of the ancient Samhain traditions survived Ireland’s conversion from paganism to Christianity, despite Pope Gregory’s best attempts to disrupt the persistent pagan elements of the celebration by renaming the November 1st holiday “All Saints’ Day” with “All Souls’ Day” to follow on November 2nd.

Eimear Clowry Delaney, the assistant director of the Dublin Global Gateway, recalls with fond memories the local bonfire gatherings of her youth (sans Druid priests and cattle sacrifices) on Halloween night where she grew up outside of Tullow, County Carlow. Irish children like Eimear did not have trick-or-treating as easy as their American counterparts; a simple “trick-or-treat!” and a smile would not do. Candy was hard won with a prepared song for every door, a truly transactional practice and a derivative of “mumming” where children went around in the days leading up to Samhain singing songs for the dead in exchange for cakes. Decades prior to Eimear’s childhood, those cakes earned in the mumming would been left out at night with the windows and doors open for dead ancestors to enjoy as the family slept.

Director Kevin Whelan’s memories of the All Hallow’s Eve of mid-century Ireland are less fond and much more frightening. His Aunt Kitty, a famous storyteller, would visit every year around the time to scare him and his siblings with “all kinds of ghost stories, of which she had an inexhaustible supply, all of them involving local people, all of them involving places that were beside us, and all of them involving things that were very scary to children.” In retrospect, he realizes that these stories were most likely a great tool to coral rambunctious children on Halloween night, but scary nonetheless. Aunt Kitty told tales of Samhain beasts that breached the barrier between Kevin’s world, the world of rural Wexford, and the spirit world. The Púca, a shape-shifting creature, was the most frightening of all. The monster often appeared as half goat, half human, bewildering travelers along the road. Kevin was sure not to wander on Halloween night, particularly down by the river behind his house as his Aunt Kitty warned, for fear of being snatched by the Púca, a sort of symbol of the devil in Kevin’s memory. But the Púca was not always so sinister; it was sometimes simply annoying. Ireland’s version of the American fashion faux pas, “no white after labor day,” comes as “no blackberries after November 1st” due to the Púca’s antics. The creature spits on wild berries as he walks, rendering them inedible from November until the next season—a hard and fast rule for an Irishman with any sense, according to Kevin.

With the mass emigration of Irish in the 19th century to North America and beyond, Samhain traditions were held tight and morphed into the recognizable Halloween celebrations we know today. While carved pumpkins replaced the traditional carved turnips and candy replaced cakes, the harvest dinner did not survive the journey across the Atlantic. An Irish Halloween dinner today is not complete without traditional dishes like colcannon—a fluffy, buttery mashed potato dish with chopped kale or cabbage and spring onion folded in. The simple dish becomes a sort of prophetic oracle on Halloween with symbolic items hidden in the mash: a thimble for spinsterhood, a button for bachelorhood, a coin for riches, and a gold ring to marry within the year. The dish is so synonymous with the holiday that it has its own jingle, “Did you ever eat colcannon?”

Another traditional Halloween treat is brack or barmbrack (see recipe below), an Irish tea cake resembling what an American might call a fruitcake. The serving of the brambrack was also used as a fortune-telling game, some loaves including up to six symbols, most of which concern themselves with one’s marriage prospects, or lack thereof. The pea meant the receiver would not marry within the year, the ring meant they would, and the stick meant an unhappy marriage was afoot. While the rag symbolized poverty, the ring symbolized riches. The less common Virgin Mary token indicated the receiver was being called to a vocation of religious life.

Since the 1980s, there has been a movement in Ireland to revive the traditional Irish elements of the now globally celebrated Halloween as it originated in those pagan Samhain celebrations. County Meath, the heart of Ireland’s ancient East, is hosting a Púca Festival with performers and light installations, harkening back to the times of sun worship and Druid priests. But the revival is not just contained within the island: The Galway based Macnas troupe travels the world with their acclaimed Halloween theatrical parades with fire spectacles and larger than life creatures more akin to those of the Samhain than today’s witches and grim reapers.

On Halloween, students at the Dublin Global Gateway are treated to an Irish Halloween dinner with all the traditional dishes. They will show up in costumes, or “fancy dress,” as they call it in Ireland. They will also participate in trivia night, a fashion show, and pumpkin carving.

Ballymaloe Barmbrack

Celebrate Halloween in its traditional form! This recipe is from Irish chef and TV personality Darina Allen’s Ballymaloe Cookery Course.

225g (8oz) dried sultanas (substitute with any dried fruit like raisins or cranberries)

225g (8oz) dried currants (substitute with any dried fruit like raisins or cranberries)

350 ml (12fl oz) strong, cold tea

1 beaten organic egg

200g (7oz) sugar

215g (7.5oz) self-raising flour

1 level teaspoon mixed spice

13 x 20cm (5 x 8in) loaf tin, lined with silicone paper

Soak the fruit in the tea overnight.

The next day preheat the oven to 180℃/350℉/gas 4.

Add the beaten egg, sugar, four and mixed spice to the fruit mixture. Pour into the prepared tin and bake in the oven for 1 hour 30 minutes. You may need to cover the top with greaseproof paper while cooking to protect it.

When cooked, brush the top with Stock Syrup and allow to cool on a wire rack. Cut into slices and serve with butter.

Enjoy!