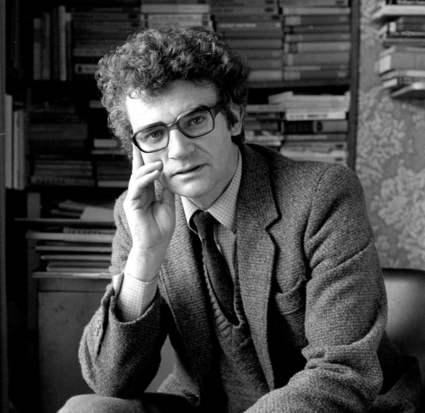

A tribute to Seamus Deane

Seamus Deane, whose death was announced earlier this week, was instrumental in building up Irish Studies at Notre Dame in the 1990s. Although an Irish identity was already hardwired into the University, Notre Dame, like Irish America in general, had anemic links with Ireland at this time.

Don Keough, then chair of the board of trustees, was the leading voice on campus, advocating that Notre Dame should develop the world’s leading Irish Studies programmes, given its deep historical connection with Irish-America and Ireland. “Build it and they will come” was what Keough presciently suggested back in 1993; how right he was.

Don made a $2.5 million gift to the University to get the programme started and tasked Christopher Fox to attract “the principal Irish intellectual at the moment” to Notre Dame. With his characteristic energy and passion, Fox persuaded Seamus Deane to become the first head of Irish Studies at Notre Dame in 1993. Deane had spent a semester teaching at Notre Dame in 1973, where among his best students was Joe Montana. He told me that Montana would easily have made a fine doctoral student.

Like Fr. Joyce and Fr. Hesburgh, Deane and Fox formed a formidable team. Seamus was a brilliant strategic thinker; Chris was indefatigable in seeking out resources and support.

Just as he had redefined Irish debate in the 1980s, Deane sought to challenge the prevalent American views of Ireland. His work had consistently interrogated “Irishness” through a stream of articles—over one hundred elegantly written essays—and books that disrupted lazy notions about the country.

Deane was often—and in my opinion, accurately—described as the most intelligent person in Ireland and—to his great amusement—his American visa recognised him as “an alien of extraordinary ability.” Along with extraordinary fluency in thought and speech, Deane possessed that rarest of gifts: a genuinely photographic memory. If you knew him well, you saw that he always paused before giving a quotation. He told me that when he was doing that, the very page he wanted flashed up on his retina just as he had first seen it, and then he simply “read” it to his audience. His lectures were delivered extempore, aided at most by three or four words written on a tiny page, or even on a matchbox.

A quality that I admired a great deal was the seriousness with which he viewed Notre Dame students. His lectures soared, ranged widely, were coherent, and made anyone listening feel they were seriously deficient in wider cultural knowledge. Deane’s range of reference was astonishing: from opera and classical music to American literature, from obscure seventeenth-century philosophers to contemporary detective fiction, from French auteur films to Moore’s melodies, from the most arcane “Theory” to the fortunes of Glasgow Celtic. (His own promising career as a stylish soccer player was terminated by a bad knee injury.)

Seamus Deane was born in 1940 in the Bogside in Derry, on the border between north and south. For centuries, the Bogside had been a festering Catholic slum, as he himself described it: "The Bogside and its neighbouring streets lay flat on the floor of a narrowed valley. Above it towards Belfast rose the walls, the Protestant cathedral, the pillared statue of Governor Walker [Protestant hero of the siege of Derry in 1690], the whole apparatus of Protestant domination. History shadowed our faces. The drifting aromas of poverty were pungent and constant reminders to the inhabitants of those upper heights that class distinction had the merciful support of geography. We lived below and between."

Deane attended St. Columb’s College in Derry. The 1960s also witnessed the first university-educated northern Catholics, who benefited from the 1947 Butler Act in the UK (an equivalent of the US G.I. Bill) that rewarded “British” working-class people for their war effort by making university education more affordable through a scholarship system. A cohort of reading activists and writers emerged from Catholic Derry, including Bernadette Devlin, Michael Farrell, Eamonn McCann, John Hume, Seamus Heaney and Seamus Deane.

Deane was part of that first cohort of Catholics to be able to proceed to university, earning a B.A. in 1961 and M.A. in 1963 from Queen’s University Belfast. Deane himself has commented: "We were the first generation to benefit from the post war educational reforms of the Labour government. My father said, “Educate yourself, I wish I had the chance. That’s the way to resist.” There was poverty, gerrymandering, discrimination, a failed political system, a great sense of isolation but no way to mobilise the anger; I felt as though I was living in a frozen sea."

Deane completed his doctorate at Cambridge in 1966, going on to teach English literature for two years at Reed College and University of California, Berkeley in the United States. He returned to Ireland to lecture at University College Dublin from 1968 to 1980. He was then appointed professor of Modern English and American literature there but became increasingly unhappy with what he regarded as the anti-intellectualism of the university.

Deane was also a poet of distinction, with three published collections. He attended school with Seamus Heaney, shared an apartment with him when they went to Queen’s together, and he remained a close friend and mentor of “Famous Seamus” over the years as his friend’s career soared. Deane himself could create memorable lines, as in his poem "Derry," "The unemployment in our bones / Erupting on our hands in stones."

He once told me that he quit writing poetry once he saw Heaney mature his great powers. Heaney sent Seamus all his collections before publication and got back rigorously precise commentary.

Deane, highly regarded as a poet, concentrated his energies on scholarly interests, marked by the rapid publication of Celtic Revivals (1985), A Short History of Irish Literature (1986) and The French Revolution and Enlightenment in England (1988)—his doctoral thesis in book form.

In 1980, Deane joined Field Day, founded by the dramatist Brian Friel and the actor Stephen Rea. The group staged a series of impressive plays across the island and Deane added an intellectual edge to its activities. During the early 1990s, he edited the transformative Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (1991), as well as a six-volume edition of Joyce’s works for the Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics series, a deliberate project to reclaim Joyce as an Irish writer.

Deane enjoyed an international reputation: Edward Said, for example, widely regarded as the founder of post-colonialism, invited him to give the keynote lecture at a conference celebrating Said’s career at his own Columbia University.

Deane’s novel, Reading in the Dark, largely written at Notre Dame, appeared in 1996. Seamus told me that his best writing time was on ND football Saturdays, when he could be sure that he would never be interrupted! Reading in the Dark is recognized as a modern classic, the most insightful novel written about the Troubles, and marked by all of Deane’s trademark intelligence, wit, and sly quotation from—and allusion to—a vast range of Irish literature.

Because it is written in a deceptively accessible style, the Gothic, post-modern and post-colonial thrust of this powerful novel has been insufficiently recognized. A striking feature of the post-partition generation of Northern Catholics was their silence: they felt cowed and alone, abandoned by both the British and Irish states, isolated in a new Protestant state where they did not wish to be and in which they were treated as suspect aliens. They became a silent, watchful, betrayed generation—”the bastard children of the Republic,” in their leader Eddie MacAteer’s striking phrase. Reading in the Dark is a brilliant ‘Troubles’ novel, all the more so because Deane showed that to understand the outbreak in the 1960s, you had to have an intimate understanding of the legacy of partition.

Seamus Deane led Irish Studies at Notre Dame from 1993 to 2004. He continued to teach every semester at the Keough Naughton Notre Dame Centre in Dublin after 2004, in both the undergraduate programme and the graduate Irish Seminar.

Seamus had a wickedly funny tongue, most creative when vituperative, and the weather always featured gusts of laughter when he was around. He loved a good conversation, and no one ever issued so many zingers. He was a loyal friend, but absolutely rigorous in his critiques when you sought his advice or commentary.

His own standards were elevated. I heard him give so many brilliant lectures that anyone else would be delighted to publish; he was just dismissive of them. Seamus came from a large and boisterous Derry family who never took him all that seriously and kept him grounded. He was a kind and supportive father, who took huge pride in the accomplishments of his children Conor, Ciarán, Cormac, Émer and Iseult.

Michael D. Higgins, President of Ireland, paid tribute to Seamus Deane’s international and American reputation this week, singling out his time at Notre Dame. He was quoted, "Seamus Deane’s participation in a seminar immediately drew huge interest from scholars young and old, partly due, no doubt, to the sheer breadth of the materials he would cover, but also due to the unique connection he would make between the life and the work."

The President also praised his contributions to Irish life: "Seamus Deane was a leading part of the great burst of intellectual revival that led to the Crane Bag, the Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature and many other innovations, which will be recalled as examples of the collaboration he had with his scholarly neighbours, and others, in giving a valuable affirmative to the importance and energy of Irish writing."

His last—and magnificent—collection of essays titled Small World will be published later this month by Cambridge University Press. While his body eventually failed him, his mind never did. Ní bhéadh a leithéid arís ann.

Kevin Whelan is the director at the Notre Dame Dublin Global Gateway and longtime friend and colleague of Seamus Deane.